References

United Nations. (n.d.). What is climate change? | United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/what-is-climate-change

Module 1 What is Migration?: Resources. (n.d.). https://wmr-educatorstoolkit.iom.int/module-1-what-is-migration-resources

International Organization for Migration. (2019). Glossary on Migration. In Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement United Nations Commission on Human Rights, E/CN.4/1998/53/Add.2.

Apap, Joanna, and Sami James Harju. “The Concept of ‘Climate Refugee.’” European Parliamentary Research Service, n.d.

Argentina.gob.ar. “Política Migratoria Argentina,” December 17, 2003. https://www.argentina.gob.ar/.

De Miguel, Teresa & Galindo, Jorge. “The destructive impacto of climate change in Mexico”. El País Mexico (2021) COP26: El destructivo impacto del cambio climático en México | EL PAÍS México (elpais.com)

Docherty, Bonnie, and Tyler Giannini. “CONFRONTING A RISING TIDE: A PROPOSAL FOR A CONVENTION ON CLIMATE CHANGE REFUGEES.” Harvard Environmental Law Review 33 (n.d.).

“El Cambio Climático Agrava La Violencia Contra Las Mujeres y Las Niñas | OHCHR.” Accessed September 26, 2024. https://www.ohchr.org/es/stories/2022/07/climate-change-exacerbates-violence-against-women-and-girls.

Enciso, Angélica. “Climate change will lead to the displacement of 3.1 million Mexicans”. La Jornada (2024)https://www.jornada.com.mx/2024/02/16/politica/014n1pol

Faret, Laurent, Andrea Paula González Cornejo, Jéssica Natalia Nájera Aguirre, and Itzel Abril Tinoco González. “The City under Constraint: International Migrants’ Challenges and Strategies to Access Urban Resources in Mexico City: Canadian Geographer.” Canadian Geographer 65, no. 4 (Winter 2021): 423–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12728.

Greenpeace Mexico. “Relocation of the El Bosque community in Tabasco is urgently needed due to rising sea levels” Greenpeace. (2023) Urge reubicación de la comunidad El Bosque, en Tabasco,ante subida del nivel del mar – Greenpeace México

Gorn, Shoshana Berenzon, Nayelhi Saavedra, Ietza Bojorquez, Geoffrey Reed, Milton L. Wainberg, and María Elena Medina-Mora. “Anxiety among Central American Migrants in Mexico: A Cumulative Vulnerability.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 6 (2023): 4899. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064899.

Hinnawi, Essam E., and UNEP. Environmental Refugees. UNEP, 1985. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/121267.

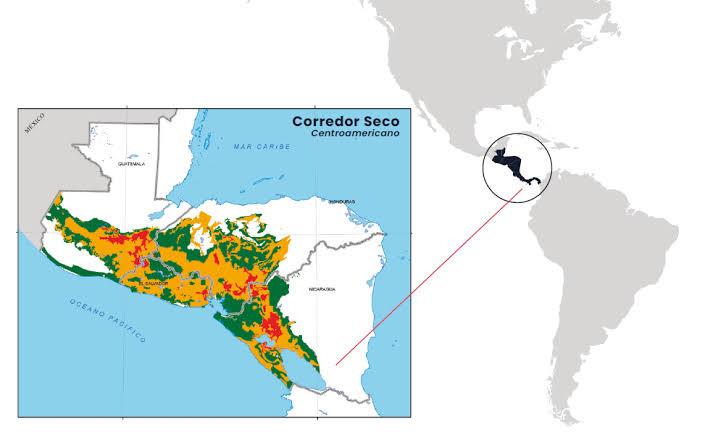

Huber, Jona, Ignacio Madurga-Lopez, Una Murray, Peter C. McKeown, Grazia Pacillo, Peter Laderach, and Charles Spillane. “Climate-Related Migration and the Climate-Security-Migration Nexus in the Central American Dry Corridor.” Climatic Change 176, no. 6 (June 16, 2023): 79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-023-03549-6.

Méndez, Ernesto. “Tabasco community of El Bosque asks IACHR for relocation due to climate change.” Excélsior. (2024)Comunidad de Tabasco acude ante CIDH para pedir reubicación por efectos de cambio climático (excelsior.com.mx)

Miguel, Jorge Alejandro Silva Rodríguez de San, Esteban Martínez Díaz, and Dulce María Monroy Becerril. “The Relationship between Climate Change and Internal Migration in the Americas.” Management of Environmental Quality 32, no. 4 (2021): 822–39. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEQ-01-2021-0020.

Risco, Javier. “The disappearance of the El Bosque community, swallowed by the sea in Tabasco”. El País Mexico (2024)La desaparición de la comunidad de El Bosque, tragada por el mar en Tabasco | Opinión | EL PAÍS México (elpais.com)

“Understanding Climate Migration with a Focus on Latin American Children and Families – ProQuest.” Accessed April 14, 2024. https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.berkeley.edu/docview/2935466390?pq-origsite=primo&sourcetype=Scholarly%20Journals.

“UNICEF Humanitarian Situation and Risks in Central American Dry Corridor (June 2023) – El Salvador | ReliefWeb,” July 20, 2023. https://reliefweb.int/report/el-salvador/unicef-humanitarian-situation-and-risks-central-american-dry-corridor-june-2023.